A Tiny Knob Keeps You In Control

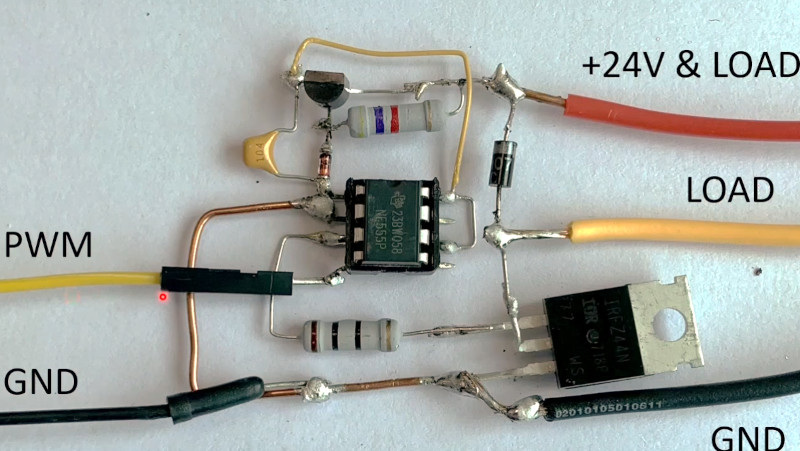

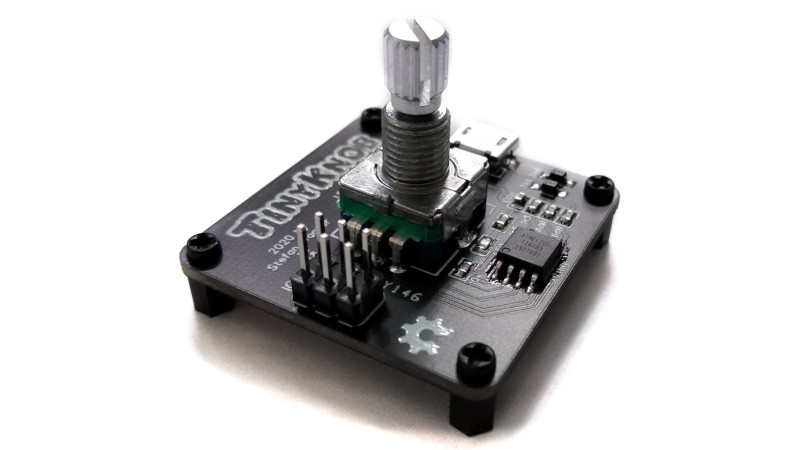

There are many forms of human interface device beyond the ubiquitous keyboard and mouse, but when it comes to fine-tuning a linear setting such as a volume control there’s nothing quite like a knob. When it comes to peripherals it’s not the size that matters, as proven by [Stefan Wagner] with the Tiny Knob. It’s a very small PCB with a rotary encoder and knob, an ATtiny85, a USB port, and not much else.

It uses the V-USB software implementation of USB HID, and should you have a need for a Tiny Knob of your own you can find all the files for it in a GitHub repository. There’s even a very professional-looking 3D-printed enclosure for the finishing touch. We like this project for its simplicity, and we think you might too.

Over the years we’ve brought you more than one knob, they appear to be a popular subject for experimentation. If you’re up for more, have a look at this one.