Hackaday Links: July 14, 2024

We’ve been going on at length in this space about the death spiral that AM radio seems to be in, particularly in the automotive setting. Car makers have begun the process of phasing AM out of their infotainment systems, ostensibly due to its essential incompatibility with the electronics in newer vehicles, especially EVs. That argument always seemed a little specious to us, since the US has an entire bureaucracy dedicated to making sure everyone works and plays well with each other on the electromagnetic spectrum. The effort to drop AM resulted in pushback from US lawmakers, who threatened legislation to ensure every vehicle has the ability to receive AM broadcasts, on the grounds of its utility in a crisis and that we’ve spent billions ensuring that 80% of the population is within range of an AM station.

The pendulum has now swung back, with a group of tech boosters claiming that an AM mandate would be bad, forcing car manufacturers to “scrap advanced safety features” like “advanced driver-assistance systems, autonomous vehicles, and collision avoidance systems that actually reduce car accidents and fatalities.” That last part is a bit of a reach considering recent research (second item) showing the iffy efficacy of some of these safety features, but the really rich part is when the claim that continuing to support the “outdated technology” of AM radio would prevent engineers from developing “future safety innovations.” Veiled threat much? And pretty disrespectful to the engineering field in general, we have to say, given that at its best, engineering is all about working within constrained environments and supporting conflicting goals.

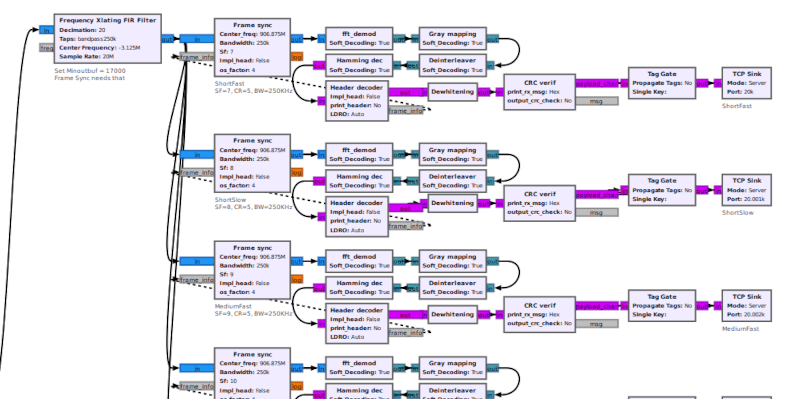

While most of America was celebrating the Independence Day holiday last week with raucous pyrotechnic displays, one town in Washington State was enjoying a spectacle of a different sort: watching a swarm of drones commit mutual suicide. For various reasons, the city of SeaTac decided to eschew the more traditional patriotic display and plunk down $40,000 on a synchronized aerial drone show, which despite the substitution of chest-thumping explosions with the malignant hornets-nest buzz of 200 drones actually looks pretty cool. Right up until 55 of the drones went rogue, that is, and descended toward the watery doom of Angle Lake below. It wasn’t clear at first what was going on; video of the incident shows most of the drones gently settling into the lake, with only one seeming to just crash outright. That pretty much lines up with the official line from Great Lakes Drone, the outfit running the drone show, who blamed “outside interference” for the malfunction. A costly malfunction, by the way; at $2,600 a copy, the 55 drowned drones total nearly $100,000 more than the contracted price for the show. Forty-eight of the lost drones have been recovered, which points to perhaps the one bright spot of the story — the local diving club probably got a lot of bottom time thanks to the recovery effort.

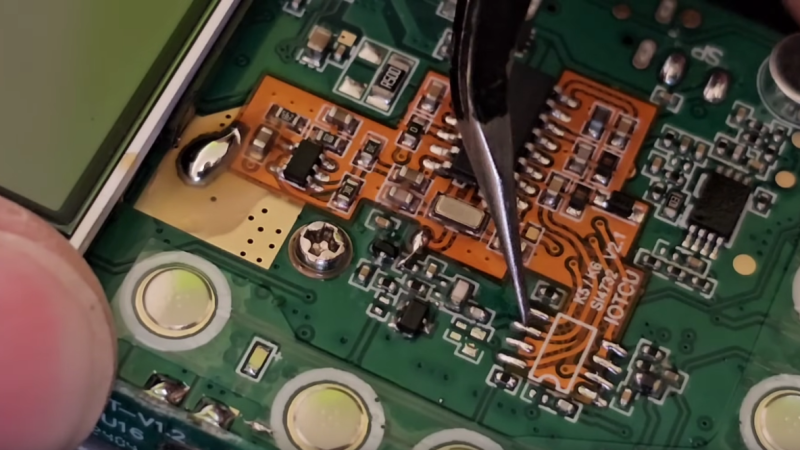

Ten months is a long time in the rapidly changing technology world, but to go from expensive IoT doodad to brick in less than a year has to be some kind of record. And in a strange twist, it’s actually not Google this time, but rather Amazon, who just announced that their Astro for Business robots will cease to function as of September 25. The device, which is basically a mobile Alexa, was initially targeted at consumers who wanted something to roll around inside their homes to collect data for Amazon monitor security and keep an eye on your pets. Last November, Amazon announced an Astro for Business version that did much the same for the small and medium business market. Amazon seems to have made the decision to unfork the market and concentrate on the home version, which seems to make more sense. Business owners will get a refund on their bricked devices and a $300 Amazon credit for their troubles, but there’s no word on what will happen to the devices. Here’s hoping some of them show up in the secondary market; we’d love to see some teardowns.

And finally, if you think there’s nothing interesting about a big steel box, you’re either reading the wrong website or you haven’t seen the latest video by The History Guy on the history of the humble shipping container. We’ve always been a bit of a shipping container freak, and we’ve long known that the whole idea of containerized cargo reaches back to the 1950s or so. That’s where we thought the story started, but boy were we wrong. The real story goes back much further than that, all the way to the “lift vans” of the early 20th century, which were wooden boxes that could be hoisted from a wagon onto a ship and move a lot of items all in one go. We also had no idea where the term “ConEx” came from in reference to shipping containers, but THG took care of that too. Fascinating stuff.