All Aboard The Good Ship Benchy

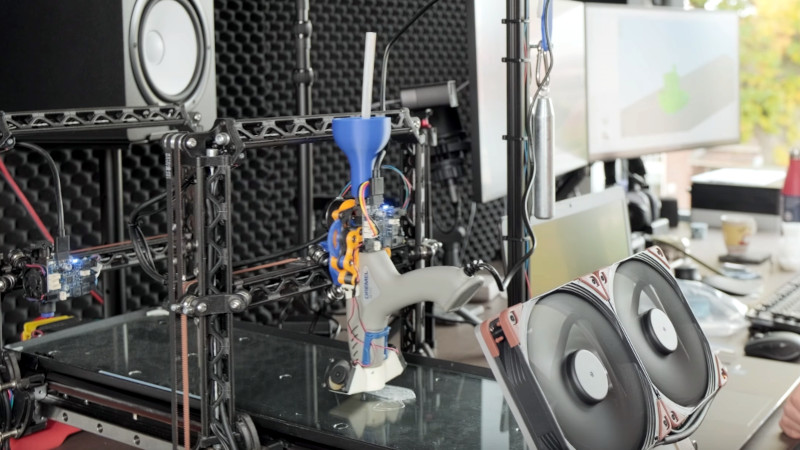

We’ll go out on a limb here and say that a large portion of Hackaday readers are also boat-builders. That’s a bold statement, but as the term applies to anyone who has built a boat, we’d argue that it encompasses anyone who’s run off a Benchy, the popular 3D printer test model. Among all you newfound mariners, certainly a significant number must have looked at their Benchy and wondered what a full-sized one would be like. Those daydreams of being captain of your ship may not have been realized, but [Dr. D-Flo] has made them a reality for himself with what he claims is the world’s largest Benchy. It floats, and carries him down the waterways of Tennessee in style!

The video below is long but has all the details. The three sections of the boat were printed in PETG on a printer with a one cubic meter build volume, and a few liberties had to be taken with the design to ensure it can be used as a real boat. The infill gaps are filled with expanding foam to provide extra buoyancy, and an aluminium plate is attached to the bottom for strength. The keel meanwhile is a 3D printed sectional mold filled with concrete. The cabin is printed in PETG again, and with the addition of controls and a solar powered trolling motor, the vessel is ready to go. Let’s face it, we all want a try!