Measuring the Mighty Roar of SpaceX’s Starship Rocket

SpaceX’s Starship is the most powerful launch system ever built, dwarfing even the mighty Saturn V both in terms of mass and total thrust. The scale of the vehicle is such that concerns have been raised about the impact each launch of the megarocket may have on the local environment. Which is why a team from Brigham Young University measured the sound produced during Starship’s fifth test flight and compared it to other launch vehicles.

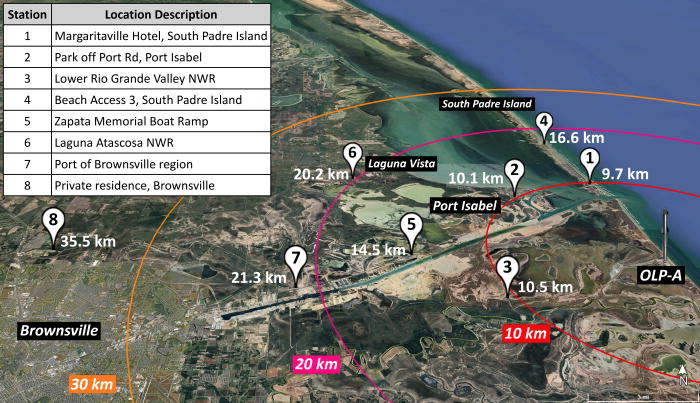

Published in JASA Express Letters, the paper explains the team’s methodology for measuring the sound of a Starship launch at distances ranging from 10 to 35 kilometers (6 to 22 miles). Interestingly, measurements were also made of the Super Heavy booster as it returned to the launch pad and was ultimately caught — which included several sonic booms as well as the sound of the engines during the landing maneuver.

The paper goes into considerable detail on how the sound produced Starship’s launch and recovery propagate, but the short version is that it’s just as incredibly loud as you’d imagine. Even at a distance of 10 km, the roar of the 33 Raptor engines at ignition came in at approximately 105 dBA — which the paper compares to a rock concert or chainsaw. Double that distance to 20 km, and the launch is still about as loud as a table saw. On the way back in, the sonic boom from the falling Super Heavy booster was enough to set off car alarms at 10 km from the launch pad, which the paper says comes out to a roughly 50% increase in loudness over the Concorde zooming by.

OK, so it’s loud. But how does it compare with other rockets? Running the numbers, the paper estimates that the noise produced during a Starship launch is at least ten times greater than that of the Falcon 9. Of course, this isn’t hugely surprising given the vastly different scales of the two vehicles. A somewhat closer comparison would be with the Space Launch System (SLS); the data indicates Starship is between four and six times as loud as NASA’s homegrown super heavy-lift rocket.

That last bit is probably the most surprising fact uncovered by this research. While Starship is the larger and more powerful of the two launch vehicles, the SLS is still putting out around half the total energy at liftoff. So shouldn’t Starship only be twice as loud? To try and explain this dependency, the paper points to an earlier study done by two of the same authors which compared the SLS with the Saturn V. In that paper, it was theorized that the arrangement of rocket nozzles on the bottom of the booster may play a part in the measured result.