As the Common Business Oriented Language, COBOL has a long and storied history. To this day it’s quite literally the financial bedrock for banks, businesses and financial institutions, running largely unnoticed by the world on mainframes and similar high-reliability computer systems. That said, as a domain-specific language targeting boring business things it doesn’t quite get the attention or hype as general purpose programming or scripting languages. Its main characteristic in the public eye appears be that it’s ‘boring’.

Despite this, COBOL is a very effective language for writing data transactions, report generating and related tasks. Due to its narrow focus on business applications, it gets one started with very little fuss, is highly self-documenting, while providing native support for decimal calculations, and a range of I/O access and database types, even with mere files. Since version 2002 COBOL underwent a number of modernizations, such as free-form code, object-oriented programming and more.

Without further ado, let’s fetch an open-source COBOL toolchain and run it through its paces with a light COBOL tutorial.

Spoiled For Choice

It used to be that if you wanted to tinker with COBOL, you pretty much had to either have a mainframe system with OS/360 or similar kicking around, or, starting in 1999, hurl yourself at setting up a mainframe system using the Hercules mainframe emulator. Things got a lot more hobbyist & student friendly in 2002 with the release of GnuCOBOL, formerly OpenCOBOL, which translates COBOL into C code before compiling it into a binary.

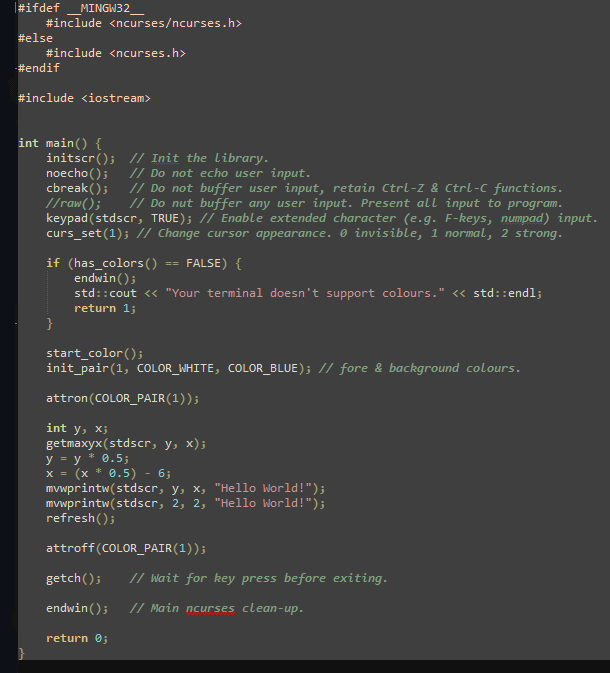

While serviceable, GnuCOBOL is not a compiler, and does not claim any level of standard adherence despite scoring quite high against the NIST test suite. Fortunately, The GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) just got updated with a brand-new COBOL frontend (gcobol) in the 15.1 release. The only negative is that for now it is Linux-only, but if your distribution of choice already has it in the repository, you can fetch it there easily. Same for Windows folk who have WSL set up, or who can use GnuCOBOL with MSYS2.

With either compiler installed, you are now ready to start writing COBOL. The best part of this is that we can completely skip talking about the Job Control Language (JCL), which is an eldritch horror that one would normally be exposed to on IBM OS/360 systems and kin. Instead we can just use GCC (or GnuCOBOL) any way we like, including calling it directly on the CLI, via a Makefile or integrated in an IDE if that’s your thing.

Hello COBOL

As is typical, we start with the ‘Hello World’ example as a first look at a COBOL application:

IDENTIFICATION DIVISION.

PROGRAM-ID. hello-world.

PROCEDURE DIVISION.

DISPLAY "Hello, world!".

STOP RUN.

Assuming we put this in a file called hello_world.cob, this can then be compiled with e.g. GnuCOBOL: cobc -x -free hello_world.cob.

The -x indicates that an executable binary is to be generated, and -free that the provided source uses free format code, meaning that we aren’t bound to specific column use or sequence numbers. We’re also free to use lowercase for all the verbs, but having it as uppercase can be easier to read.

From this small example we can see the most important elements, starting with the identification division with the program ID and optionally elements like the author name, etc. The program code is found in the procedure division, which here contains a single display verb that outputs the example string. Of note is the use of the period (.) as a statement terminator.

At the end of the application we indicate this with stop run., which terminates the application, even if called from a sub program.

Hello Data

As fun as a ‘hello world’ example is, it doesn’t give a lot of details about COBOL, other than that it’s quite succinct and uses plain English words rather than symbols. Things get more interesting when we start looking at the aspects which define this domain specific language, and which make it so relevant today.

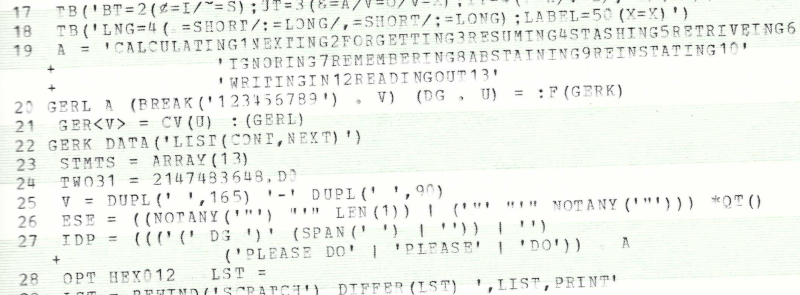

Few languages support decimal (fixed point) calculations, for example. In this COBOL Basics project I captured a number of examples of this and related features. The main change is the addition of the data division following the identification division:

DATA DIVISION.

WORKING-STORAGE SECTION.

01 A PIC 99V99 VALUE 10.11.

01 B PIC 99V99 VALUE 20.22.

01 C PIC 99V99 VALUE 00.00.

01 D PIC $ZZZZV99 VALUE 00.00.

01 ST PIC $*(5).99 VALUE 00.00.

01 CMP PIC S9(5)V99 USAGE COMP VALUE 04199.04.

01 NOW PIC 99/99/9(4) VALUE 04102034.

The data division is unsurprisingly where you define the data used by the program. All variables used are defined within this division, contained within the working-storage section. While seemingly overwhelming, it’s fairly easily explained, starting with the two digits in front of each variable name. This is the data level and is how COBOL structures data, with 01 being the highest (root) level, with up to 49 levels available to create hierarchical data.

This is followed by the variable name, up to 30 characters, and then the PICTURE (or PIC) clause. This specifies the type and size of an elementary data item. If we wish to define a decimal value, we can do so as two numeric characters (represented by 9) followed by an implied decimal point V, with two decimal numbers (99). As shorthand we can use e.g. S9(5) to indicate a signed value with 5 numeric characters. There a few more special characters, such as an asterisk which replaces leading zeroes and Z for zero suppressing.

The value clause does what it says on the tin: it assigns the value defined following it to the variable. There is however a gotcha here, as can be seen with the NOW variable that gets a value assigned, but due to the PIC format is turned into a formatted date (04/10/2034).

Within the procedure division these variables are subjected to addition (ADD A TO B GIVING C.), subtraction with rounding (SUBTRACT A FROM B GIVING C ROUNDED.), multiplication (MULTIPLY A BY CMP.) and division (DIVIDE CMP BY 20 GIVING ST.).

Finally, there are a few different internal formats, as defined by USAGE: these are computational (COMP) and display (the default). Here COMP stores the data as binary, with a variable number of bytes occupied, somewhat similar to char, short and int types in C. These internal formats are mostly useful to save space and to speed up calculations.

Hello Business

In a previous article I went over the reasons why a domain specific language like COBOL cannot be realistically replaced by a general language. In that same article I discussed the Hello Business project that I had written in COBOL as a way to gain some familiarity with the language. That particular project should be somewhat easy to follow with the information provided so far. New are mostly file I/O, loops, the use of perform and of course the Report Writer, which is probably best understood by reading the IBM Report Writer Programmer’s Manual (PDF).

Going over the entire code line by line would take a whole article by itself, so I will leave it as an exercise for the reader unless there is somehow a strong demand by our esteemed readers for additional COBOL tutorial articles.

Suffice it to say that there is a lot more functionality in COBOL beyond these basics. The IBM ILE COBOL reference (PDF), the IBM Mainframer COBOL tutorial, the Wikipedia entry and others give a pretty good overview of many of these features, which includes object-oriented COBOL, database access, heap allocation, interaction with other languages and so on.

Despite being only a novice COBOL programmer at this point, I have found this DSL to be very easy to pick up once I understood some of the oddities about the syntax, such as the use of data levels and the PIC formats. It is my hope that with this article I was able to share some of the knowledge and experiences I gained over the past weeks during my COBOL crash course, and maybe inspire others to also give it a shot. Let us know if you do!

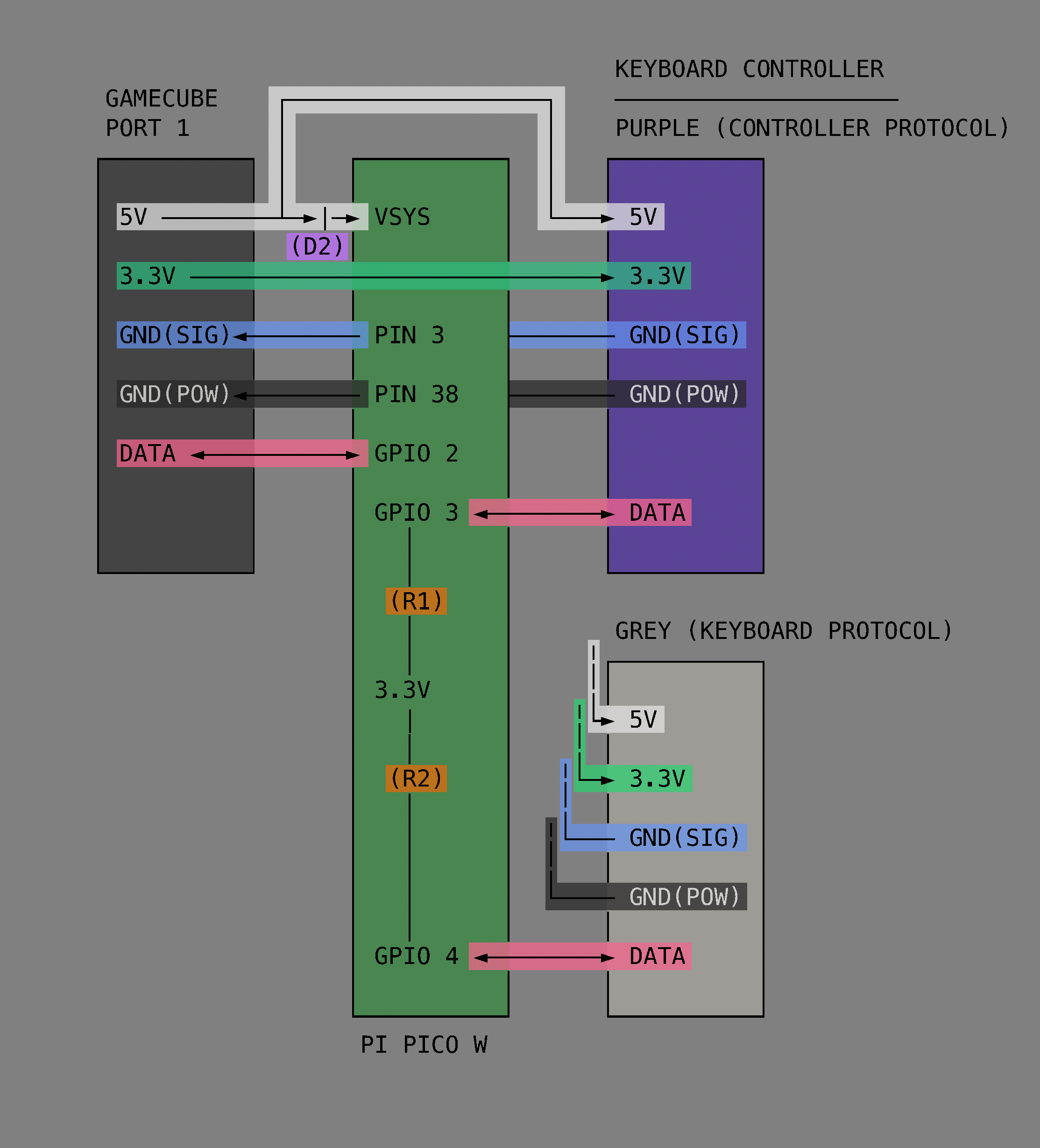

In this project [Hunter] intercepts the controller protocol and the keyboard protocol with a Raspberry Pi Pico and then forwards them along to an attached GameCube by emulating a standard controller from the Pico. Having got that to work [Hunter] then went on to add a bunch of extra features.

In this project [Hunter] intercepts the controller protocol and the keyboard protocol with a Raspberry Pi Pico and then forwards them along to an attached GameCube by emulating a standard controller from the Pico. Having got that to work [Hunter] then went on to add a bunch of extra features.