Close Shave for an Old Oscilloscope Saved with a Sticky Note

When you tear into an old piece of test equipment, you’re probably going to come up against some surprises. That’s especially true of high-precision gear like oscilloscopes from the time before ASICs and ADCs, which had to accomplish so much with discrete components and a lot of engineering ingenuity.

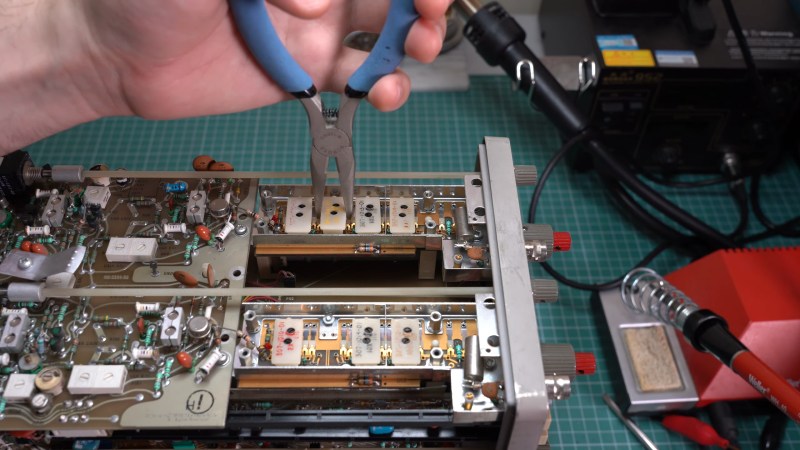

Unfortunately, though, those clever hacks that made everything work sometimes come back to bite you, as [Void Electronics] learned while bringing this classic Tektronix 466 scope back to life. A previous video revealed that the “Works fine, powers up” eBay listing for this scope wasn’t entirely accurate, as it was DOA. That ended up being a bad op-amp in the power supply, which was easily fixed. Once powered up, though, another, more insidious problem cropped up with the vertical attenuator, which failed with any setting divisible by two.

With this curious symptom in mind, [Void] got to work on the scope. Old analog Tek scopes like this use a bank of attenuator modules switched in and out of the signal path by a complex mechanical system of cams. It seemed like one of the modules, specifically the 4x attenuator, was the culprit. [Void] did the obvious first test and compared the module against the known good 4x module in the other channel of the dual-channel scope, but surprisingly, the module worked fine. That meant the problem had to be on the PCB that the module lives on. Close examination with the help of some magnification revealed the culprit — tin whiskers had formed, stretching out from a pad to chassis ground. The tiny metal threads were shorting the signal to ground whenever the 4x module was switched into the signal path. The solution? A quick flick with a sticky note to remove the whiskers!

This was a great fix and a fantastic lesson in looking past the obvious and being observant. It puts us in the mood for breaking out our old Tek scope and seeing what wonders — and challenges — it holds.