Handheld Satellite Dish is 3D Printed

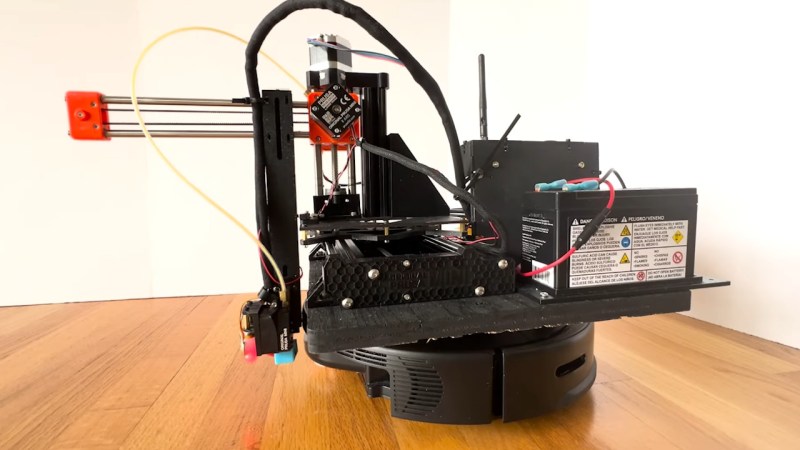

Ham radio enthusiasts, people looking to borrow their neighbors’ WiFi, and those interested in decoding signals from things like weather satellites will often grab an old satellite TV antenna and repurpose it. Customers have been leaving these services for years, so they’re pretty widely available. But for handheld operation, these metal dishes can get quite cumbersome. A 3D-printed satellite dish like this one is lightweight and small enough to be held, enabling some interesting satellite tracking activities with just a few other parts needed.

Although we see his projects often, [saveitforparts] did not design this antenna, instead downloading the design from [t0nito] on Thingiverse. [saveitforparts] does know his way around a satellite antenna, though, so he is exactly the kind of person who would put something like this through its paces and use it for his own needs. There were a few hiccups with the print, but with all the 3D printed parts completed, the metal mesh added to the dish, and a correctly polarized helical antenna formed into the print to receive the signals, it was ready to point at the sky.

The results for the day of testing were incredibly promising. Compared to a second satellite antenna with an automatic tracker, the handheld 3D-printed version captured nearly all of the information sent from the satellite in orbit. [saveitforparts] plans to build a tracker for this small dish to improve it even further. He’s been able to find some satellite trackers from junked hardware in some unusual places as well. Antennas seem to be a ripe area for 3D printing.