Keeping Track of Old Computer Manuals with the Manx Catalog

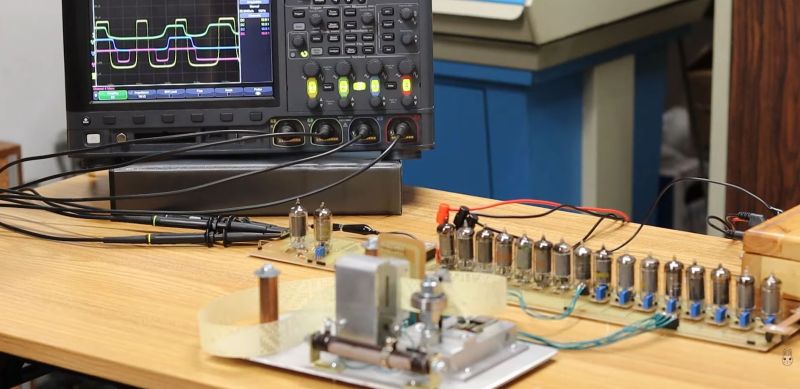

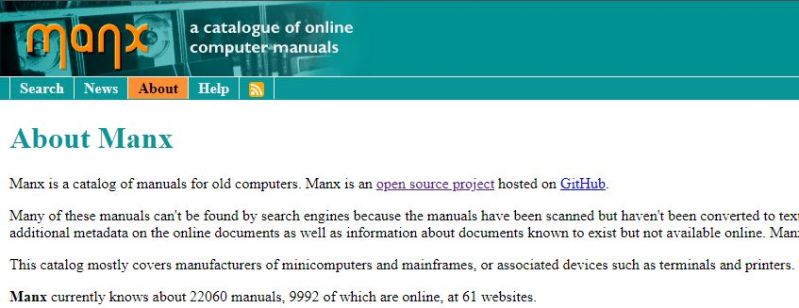

An unfortunate reality of pre-1990s computer systems is that any manuals and documentation that came with them likely only existed on paper. That’s not to say there aren’t scanned-in (PDF) copies of those documents floating around, but with few of these scans being indexable by search engines like Google and Duck Duck Go, they can be rather tricky to find. That’s where the Manx catalog website seeks to make life easier. According to its stats, it knows about 22,060 manuals (9,992 online) across 61 websites, with a focus on minicomputers and mainframes.

The code behind Manx is GPL 2.0 licensed and available on GitHub, which is where any issues can be filed too. While not a new project by any stretch of the imagination, it’s yet another useful tool to find a non-OCR-ed scan of the programming or user manual for an obscure system. As noted in a recent Hacker News thread, the ‘online’ part of the above listed statistics means that for manuals where no online copy is known, you get a placeholder message. Using the Bitsavers website along with Archive.org may still be the most pertinent way to hunt down that elusive manual, with the Manx website recommending 1000bit for microcomputer manuals.

Have you used the Manx catalog, or any of the other archiving websites? What have been your experiences with them? Let us know in the comments.