Gaming Table has Lights, Action

We couldn’t decide if [‘s] Dungeons and Dragons gaming table was a woodworking project with some electronics or an electronics project with some woodworking. Either way, it looks like a lot of fun.

Some of the features are just for atmosphere. For example, the game master can set mood lighting. Presets can have a particular light configuration for, say, the woods or a cave.

But the table can also be a game changer since the game runner can send private messages to one or more players. Imagine a message saying, “You feel strange and suddenly attack your own team without any warning.”

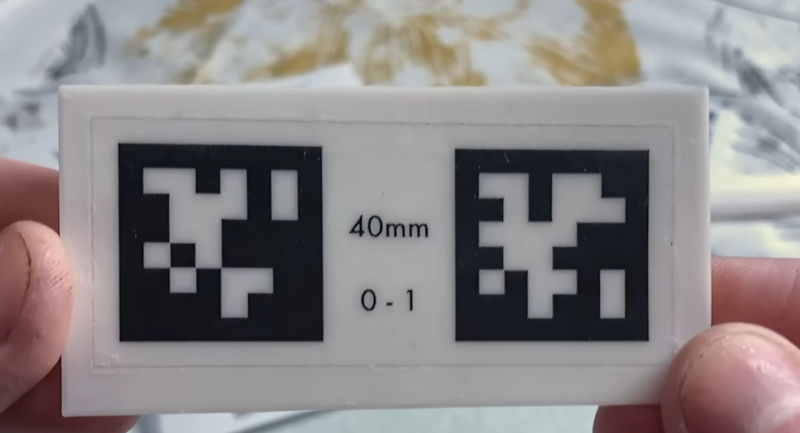

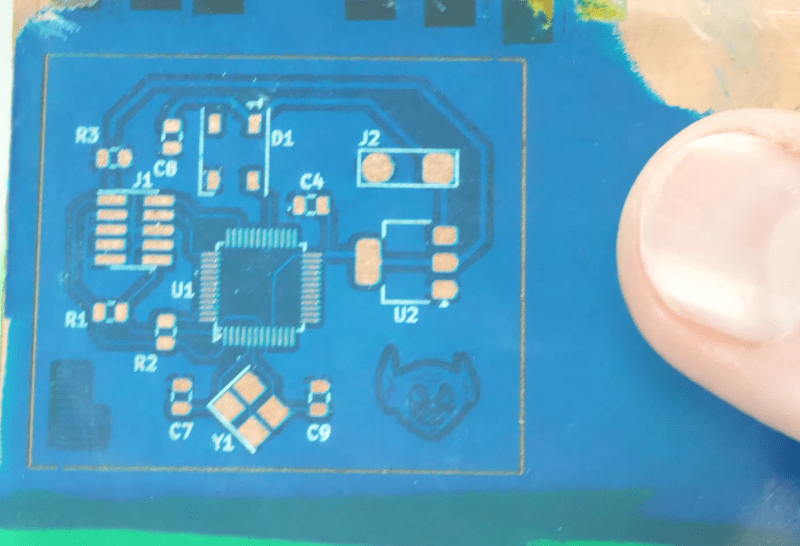

A series of ESP32 chips makes it possible. The main screen has an IR touch frame, and the players have smaller screens. The main screen shows an HTML interface that lets you set initiatives, send messages, and control the lighting. Each player also has an RFID reader that the players use to log in.

The ESP32 chips use ESP-NOW for simplified networking. Of course, you could just have everyone show up with a laptop and have some web-based communications like that, but the table seems undeniably cool.

Usually, when we see a gaming table, the table itself is the game. If we were building a D&D table, we might consider adding a printer.