Fictional Computers: EMERAC was the Chatbot of 1957

Movies mirror the time they were made. [ErnieTech] asserts that we can see what people thought about computers back in 1957 by watching the classic Spencer Tracy/Katharine Hepburn movie “Desk Set.” What’s more, he thinks this might be the first movie appearance of a human-like computer. On a side note, in the UK this movie was known as “The Other Woman.”

The story is about an MIT computer expert computerizing a broadcasting company who, of course, finds romance and, at least towards the end, comedy.

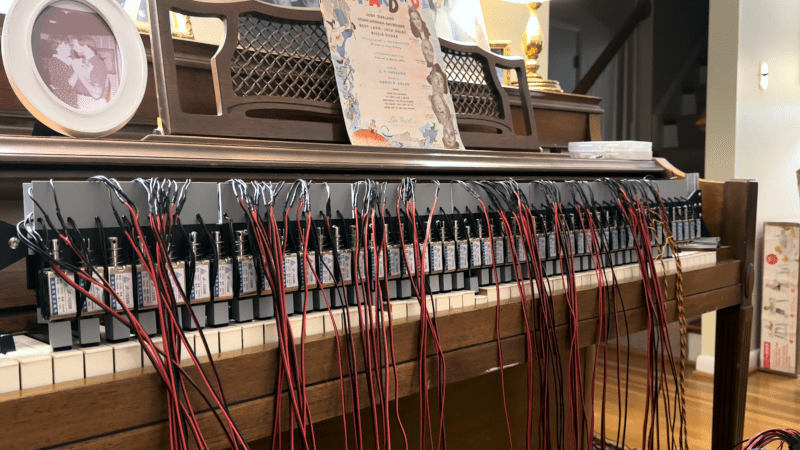

Of course, we are interested in the computer. It was supposedly an IBM machine and while IBM apparently provided some equipment (probably typewriters and tape drives), the computer is clearly just a ton of light bulbs. It was named Emmie, which was a nickname for EMERAC. Oddly enough, it was about like a modern web search engine or chatbot, answering random research questions. The difference is they had fed all the world’s knowledge into it themselves using punched cards.

The video has spoilers, but for a movie made in 1957, that’s not really an issue. The ending is pretty predictable, anyway. Like many people in 1957, there was a fear that “computers were going to take all our jobs!” [Ernie] makes the point that this was a common trope where the computer would run the Enterprise company and then made a big mistake, and everyone realized we still needed humans. EMERAC later guest-starred in the movie “The Fly.” It was just a background player in the chorus, though.

He also points out that many of the things people thought about the widespread adoption of computers are still true today if you replace computer with AI. Turns out, you still need to know how to reset the system.

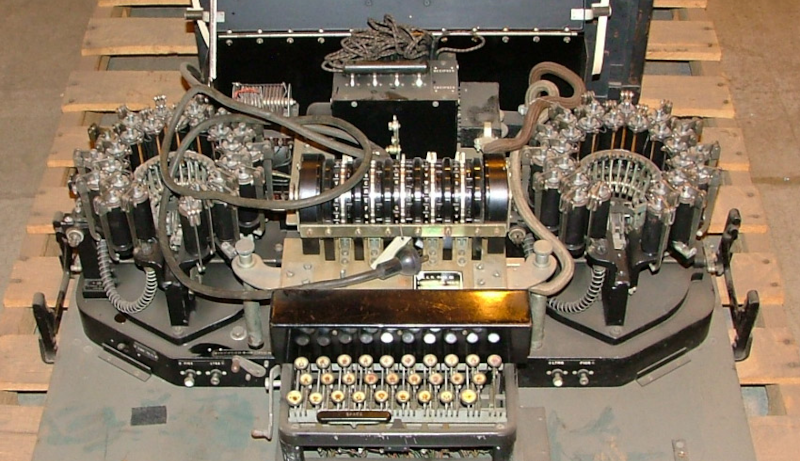

[Ernie] did a video about Colossus last month, a topic we also visited last year. One of our favorite fictional computers, though, was more recent from “The Three Body Problem.”